And They Called It Vancouver

Settler-Colonial Relationships to Indigenous Lands and Peoples

Urban Development

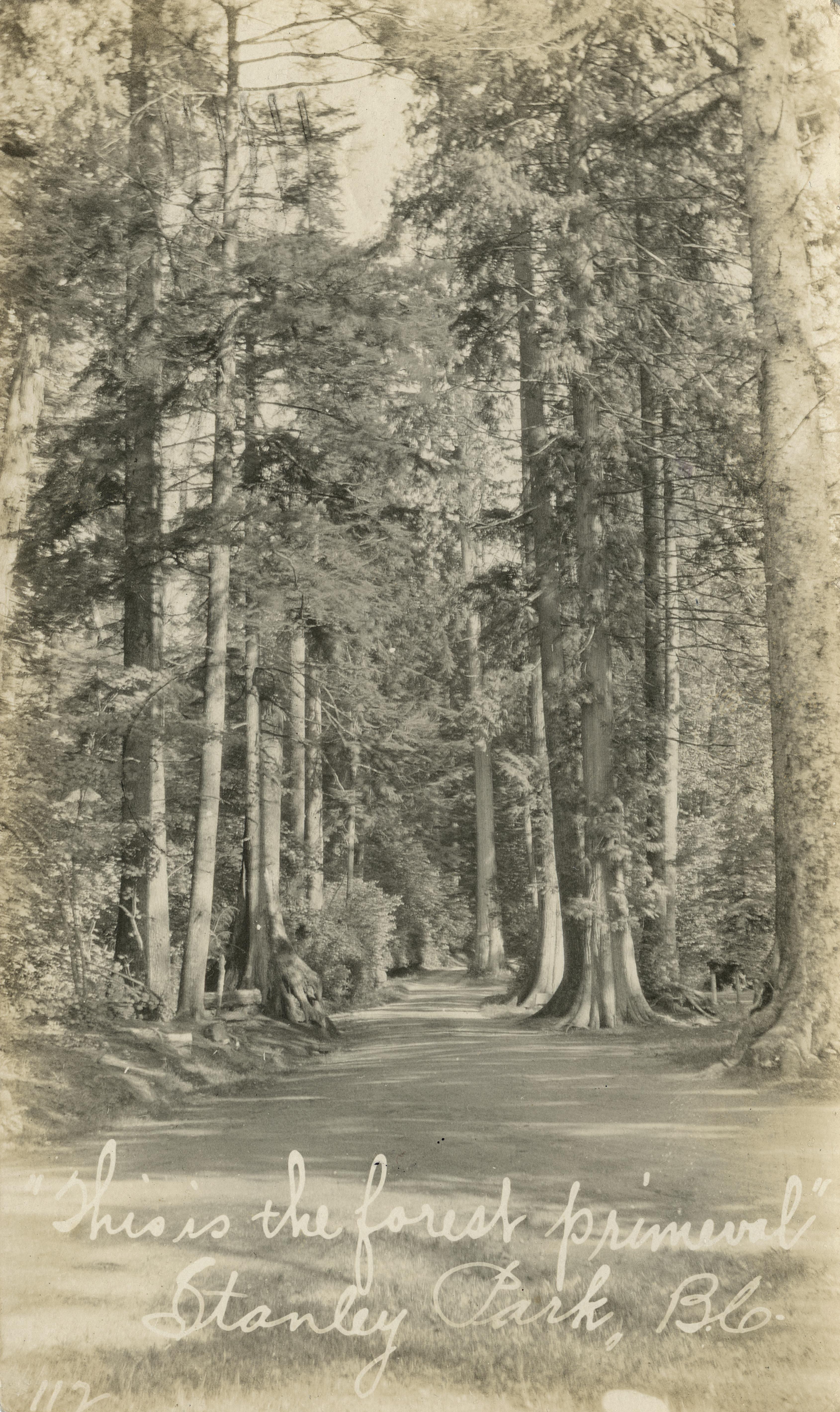

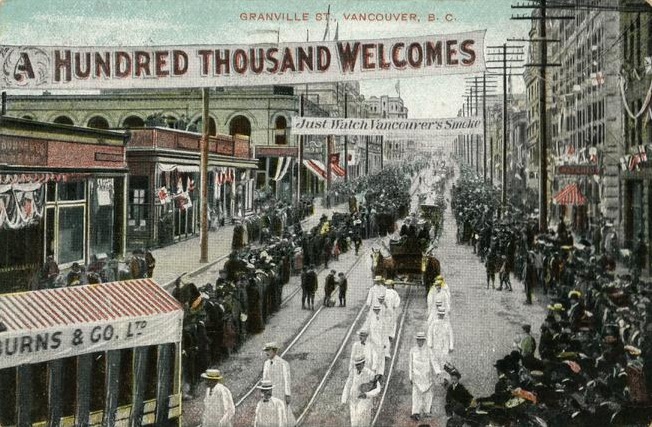

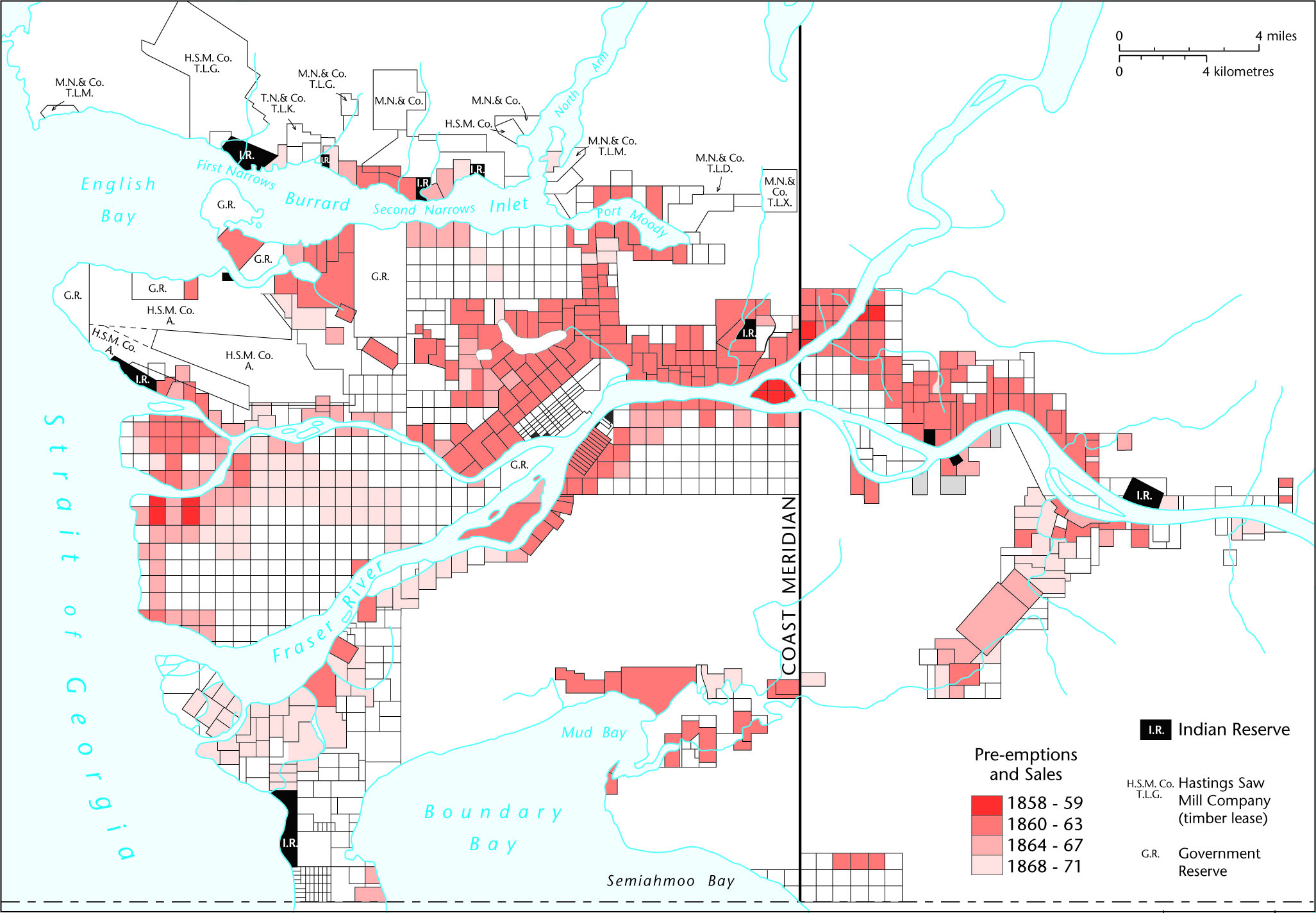

An important piece of the context surrounding the photographs in this section is the way in which White settlers around the turn of the twentieth century viewed urban development and control of nature. As local Tyee journalist Jesse Donaldson explains in his article, An Unnatural History of Stanley Park, the prevailing philosophy of the time “considered the wilderness something to be tamed and cultured, an ‘improved’ version of nature manicured by human intervention.”1 This “improvement” of nature was another part of the colonial fairy tale, as characterized by Paige Raibmon, an associate professor of history at the University of British Columbia. The dominant settler perspective required this narrative to be accepted in order to justify their takeover of Indigenous lands. They had to first believe the lands that became Vancouver were completely pure and unsettled before they took over, actively supressing the societies that existed before and continued to exist after their arrival. Second, they had to believe urbanization and industrialization were positive steps towards progress, in order to view themselves as saviors rather than destroyers.2</sup The fairy tale went one step further. Settlers wanted to create an example near the city of their control over nature, an urban park that would “transform the image of Vancouver to be more than just another boomtown.”3 The area now known as Stanley Park became the chosen space to create this fantasy. However, some mental gymnastics were required to transform Stanley Park in the public imagination into an uncultivated landscape. The reality was that, far from being the “primeval forest” that settlers imagined it to be, the area had long been the site of a thriving populace of Indigenous peoples. “The Aboriginal presence on the peninsula was considerable on the eve of the imposition of Stanley Park in 1887. Whatever may have been the land’s official status, Aboriginal people still considered it their own. For some… it was a place of residence. For others, it served economic and spiritual purposes [including as a burial ground].”4 This section of the exhibition features images that act as evidence of this colonial fairy tale, and depicts the settler-colonial gaze on the lands they had taken over. It also showcases snapshots of the city, and the confidence and speed with which settlers developed the area into their idea of what a modern metropolis should be. This image to the left, taken from Coal Harbour and looking toward Deadman’s Island sometime between 1891 and 1901, shows settlements along the shore of the island. The image to the right shows similar establishments on the other side of the park, at English Bay. When this area was transformed into Stanley Park, habitations such as these were destroyed, and their residents forced to relocate. The historian Jean Barman, in her book Stanley Park’s Secret shares quotes from Indigenous individuals who lived on these lands before their forced relocation. In one case, a man named August Jack shares his experience of his house literally being demolished while he was inside. The house was located on the site of a future road that would wrap around the perimeter of Stanley Park, and would have been similar to the houses pictured here. “We was inside this house when the surveyors come along, and they chop the corner of our house when we was eating inside.”5 Another slightly more puzzling sign in the background reads “Just Watch Vancouver’s Smoke.” This could be an indication of the way in which industrialization was revered, and environmental impact was not yet the subject of widespread concern – at least not by settlers. These triumphant aerial shots portray the sprawling, newly erected buildings of Vancouver’s downtown hub. However, not everyone was permitted to share in the perceived progress of the young city. By the time Vancouver was developing as a major city, Indigenous peoples had already faced a long history of marginalization. Erin Hanson, a researcher of Coast Salish law at UBC’s Department of Anthropology, notes in Aboriginal Rights: “Colonial governments in Canada initially practiced a policy of extinguishment, which meant that Aboriginal peoples’ rights would be surrendered or legislated away, often in exchange for treaty rights…. Over time, however, many Aboriginal people found that the Canadian state continued to subjugate them and infringe upon the very rights they thought would be respected…. For example, the government added specific pieces of discriminatory legislation in the Indian Act that made it illegal for Aboriginal people to organize politically or to hire legal counsel to further land claims.”6 In this way, Indigenous peoples were forced to watch their traditional and ancestral homelands give way to settlements they were forcibly excluded from, such as those pictured above, while any power they had to seek redress was also stripped away. As noted by the Museum of Anthropology’s Musqueam Teaching Kit, “The government amended the Indian Act in 1927 making it illegal for us to hire lawyers and hold meetings to pursue land claims. Despite this injustice, First Nations worked together to form the Native Brotherhood of British Columbia and other political organizations to assert our Aboriginal rights.”7 Jordan Stanger-Ross, associate professor of history at the University of Victoria and director of the Landscapes of Injustice research project, discusses the idea that there has been a historical “opposition assumed between the civilization cities are imagined to represent, and the imagined savageness of Indigenous people…. There is an idea that the two can’t coexist.”8 For this reason, when settlers designated lands for First Nations reserves, those lands were often not centrally located near developing urban hubs. “If you look at where reserves have been placed in this country, they’re largely on the outskirts,” says Ginger Gosnell-Myers of the Nisga’a and Kwakwak'awakw Nations, and Indigenous Relations Manager at the City of Vancouver. “That’s by design... we’re looking at a deliberate history of exclusion.”9 This image demonstrates that the rapid development of the new city was largely orchestrated by settlers of European descent. However, much of the hard labour was carried out by immigrants, usually of East and South Asian origin. This was true for projects across B.C., including the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway. Chinese immigrants made up the majority of railway workers and were paid less than their White counterparts, as well as being given the most dangerous tasks, which led to a higher rate of accidents and deaths.11 Despite being an integral part of creating the railway that would connect British Columbia to the rest of Canada, Asian immigrants experienced discrimination, segregation, and disenfranchisement by the federal government and White settlers for decades. There is a long history of symbiotic, respectful relationships between Chinese immigrants and Indigenous communities, even predating B.C. Confederation.12

Metadata CSV

Metadata JSON

Geodata JSON

Timeline JSON

Facets JSON

Source Code

Perhaps the best example of the colonial-settler attitude towards progress and urban development, this illustration for the Golden Jubilee features two versions of the Vancouver skyline, one before skyscrapers and buildings were erected, and one after. The juxtaposition of the two skylines, in addition to the adjectives used in the text, provide an example of settler values at that time.

Image description: An illustration depicting two versions of the Vancouver skyline, one from 1886 and one from 1936, with a short statement lauding urban development.

Source: Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. UL_1624_02_0239. Rare Books and Special Collections.

The handwritten caption on this photograph of a tall row of trees, reading “This is the forest primeval,” provides further evidence of the cognitive dissonance their actions required when it came to Stanley Park in particular.

Image description: View of path through forest of Stanley Park. Written on photograph: 112. Handwritten caption reads: This is the forest primeval, Stanley Park, B.C.

Source: Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. UL_1624_02_0102. Rare Books and Special Collections.

Left: View toward settlements on Deadman's Island from Coal Harbour.

Source: Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. UL_1015_0080. Rare Books and Special Collections.

Right: A view of driftwood on the beach, with buildings in the background and the tall trees of Stanley Park in the far background.

Source: Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. UL_1015_0012. Rare Books and Special Collections.

Source: Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. UL_1662_0001. Rare Books and Special Collections.

Left: View of buildings being constructed in downtown Vancouver.

Source: Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. UL_1624_03_0227. Rare Books and Special Collections.

Right: Aerial view of Vancouver, B.C.

Source: Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. UL_1624_03_0228. Rare Books and Special Collections.

Permission for use of this image in this exhibition was granted by Eric Leinberger.

Indigenous lands, including sacred areas and burial grounds, were taken over and transformed into sites of leisure and social gathering for colonial settlers. This image portrays a busy day at Second Beach in Stanley Park, where settlers in suits and dresses walk, gather, and sun- and ocean-bathe. The tall trees of Stanley Park can be seen in the background.

Source: Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. UL_1639_0015. Rare Books and Special Collections.

Source: Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. UL_1624_03_0313. Rare Books and Special Collections.

Source: Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. UL_1628_0026. Rare Books and Special Collections.Collection as Data (click to download)

2. For a more nuanced discussion about the various groups of people that have historically fallen under the umbrella category of settler, please see the Note on Terminology in the About page.

3. Jean Barman, Stanley Park’s Secret: The Forgotten Families of Whoi Whoi, Kanaka Ranch and Brockton Point (Madeira Park, BC: Harbour Publishing, 2005), 90.

4. Ibid, 45.

5. Ibid, 92.

6. Erin Hanson, “Aboriginal Rights,” Indigenous Foundations, accessed November 13, 2020, https://indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/aboriginal_rights/.

7. “Historic Timeline,” Museum of Anthropology Musqueam Teaching Kit, accessed December 14, 2020, http://www2.moa.ubc.ca/musqueamteachingkit/history.php.

8. Matthew Halliday, “The bold new plan for an Indigenous-led development in Vancouver,” The Guardian, January 3, 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2020/jan/03/the-bold-new-plan-for-an-indigenous-led-development-in-vancouver.

9. Ibid.

10. Chuck Davis, “Vancouver, British Columbia,” accessed December 14, 2020, https://www.britannica.com/place/Vancouver.

11. “Discrimination,” British Columbia, accessed January 22, 2021, https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/governments/multiculturalism-anti-racism/chinese-legacy-bc/history/discrimination.

12. Justine Hunter, “A forgotten history: tracing the ties between B.C.'s First Nations and Chinese workers,” The Globe and Mail, May 9, 2015, https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/british-columbia/chinese-heritage/article24335611/.

![[Illustration for the Golden Jubilee of Vancouver]](/langmann-2021/objects/ul_1624_02_0239.jpg)