And They Called It Vancouver

Settler-Colonial Relationships to Indigenous Lands and Peoples

Environmental Impact

The prevailing attitude of colonial-settlers around the turn of the twentieth century saw urban development and the taming of nature as the unquestioned goals of a progressive, modern society. This ethos both fueled and justified their moves towards logging and mass deforestation, as well as factory development that resulted in air and water pollution. Ken Drushka, a forestry author, columnist, and critic, explains the attitudes about forests that were prevalent amongst Eurowestern settlers in early Canada:

“At best, conventional wisdom was ambivalent when it came to consideration of forests. At worst, they were seen as evil impediments to civilization that should be eliminated as quickly and efficiently as possible. Most European colonists brought with them to the so-called New World a cultural antipathy to forests. Their myths, legends, and literature abounded with images of forests as dangerous places. These stereotypes were reinforced in North America.”1

Mass deforestation began to escalate in Canada, partly due to this ethos, and partly because of a global demand for lumber that the British crown realized it could use for monetary gain.2 The result was that, “in 1900, the state of Canada’s forests was at its lowest point since the period of glaciation.”3 Conservation efforts in the 20th century ensured that deforestation did not continue at the same devastating rate, which means that the record low reached in 1900 remains the lowest point in history.

Max Liboiron, a Métis/Michif leader in anticolonial research methods, discusses how settlers’ lack of responsible custodianship of the land is inextricably tied to the treatment of the peoples indigenous to those lands. “Canada’s extraction economy” they say, “from fur to fossil fuels – has been at the forefront of Canadian disruptions to Indigenous Land and self-determination. The pollution from extraction, as well as from refining, manufacturing, and other industries, is often concentrated in Indigenous communities, becoming a form of intergenerational violence.”4

Leona Sparrow, the director of Treaty, Lands and Resources for the Musqueam Indian Band, also explains the impact of colonization of Indigenous lands: “Europeans took this land over and over and over, until we were cornered in this little spot. It’s been decimating in terms of access to territory. A lot of restrictions were enforced through the Indian Act and through being a part of the City of Vancouver without choice, without consultation. That’s been pretty traumatic for the community.”5

White Earth Ojibway writer and environmental activist Winona LaDuke explains the depth of the connection between Indigenous peoples and the land.

Native American teachings describe the relations all around – animals, fish, trees, and rocks -- as our brothers, sisters, uncles, and grandpas. Our relations to each other, our prayers whispered across generations to our relatives, are what bind our cultures together. The protection, teachings, and gifts of our relatives have for generations preserved our families. These relations are honored in ceremony, song, story, and life that keep relations close—to buffalo, sturgeon, salmon, turtles, bears, wolves, and panthers. These are our older relatives—the ones who came before and taught us how to live. Their obliteration by dams, guns, and bounties is an immense loss to Native families and cultures. Their absence may mean that a people sing to a barren river, a caged bear, or buffalo far away. It is the struggle to preserve that which remains and the struggle to recover that characterizes much of Native environmentalism. It is these relationships that industrialism seeks to disrupt. Native communities will resist with great determination.6

The images in this section portray settler-colonialists’ attitudes towards custodianship of the natural environment. For them, there was little meaningful consideration, respect or understanding of Indigenous peoples’ relationships to the land. In some instances, tokenistic efforts were taken to collect Indigenous peoples’ input on issues such as land rights, but any knowledge gained was cast aside in order to continue furthering the proprietary and monetary gains of the colonial government. One such instance was the McKenna McBride Commission (1912-1916), wherein the Canadian and British Columbian governments aimed to visit each First Nations community in B.C. with the goal of consulting them about their land needs and assigning more lands to reserves as needed.7 Although many Indigenous communities expressed their needs for more agency over their lands, as well as for treaties, the results of the commission added some lands while taking away others, particularly those in urban areas with high economic potential.8 Several First Nations in British Columbia banded together to form the Allied Indian Tribes and resist the results of the commission, as well as new oppressive measures that the government had put in place, but while this joint effort revealed “the power of unity that existed among all the B.C. Indian Tribes at that time,” the commission simply reacted by cracking down harder and introducing new legislation in a 1929 amendment to the Indian Act that made it illegal for Indigenous peoples to pursue their land rights in any way, including raising money, hiring a lawyer, or even meeting amongst themselves to talk about land claims. Control, modernization, and exploitation remained the main factors in the colonial project, and the McKenna-McBride Commission became one more example of how any competing views were systematically erased through policies of white supremacy.

Top-left: A snowy field filled with hundreds of logs lying on their side in the foreground. In the background, a logging mill can be seen, among other buildings.

Source: Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. UL_1639_0012_02. Rare Books and Special Collections.

Top-right: View of piles of cut logs in the forest. A man can be seen standing on top of a small pile in the bottom right.

Source: Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. UL_1639_0012_03. Rare Books and Special Collections.

Bottom: View of logs coming down the river. In the background, logged areas on the bank of the river can be seen, with other trees still standing in the far background.

Source: Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. UL_1639_0035. Rare Books and Special Collections.

Not only was mass logging taking place in British Columbia, but the existence of these photographs indicate that there may have been public demand for evidence of such activities. Photographers documented the process of deforestation in the service of creating a city, or for the creation of an economic infrastructure based on resource extraction and exploitation. One can imagine how average settlers might have enjoyed seeing evidence of the “modernization” of the land they had overtaken. It is important to note as well that the very idea of land as property was a product of colonization, and that Indigenous peoples had a very different relationship to the land, one that emphasized harmony. As Daniel Heath Justice, professor and Canada Research Chair in Indigenous Literature and Expressive Culture at the University of British Columbia, explains, “Other-than-human beings go about their lives as we go about ours; these plants, animals, stones, and other presences are our seen and unseen relatives, our neighbours, our friends or companions….”9 This would have stood in sharp contrast to the Eurowestern settler idea of manifest destiny, the belief that god has created natural resources for human exploitation.

While the prevailing attitude of settlers was one that justified a colonial takeover of Indigenous lands, as well as mass logging, mining, and other activities to extract precious resources, not everyone was entirely comfortable accepting this narrative. Colonel Moody, the first Lieutenant-Governor of British Columbia, declared of the land at New Westminster: it was “magnificent beyond description…. I declare without the least sentimentality, I grieve and mourn the ruthless destruction of these most glorious trees. What a grand old park this whole hill would make.”10

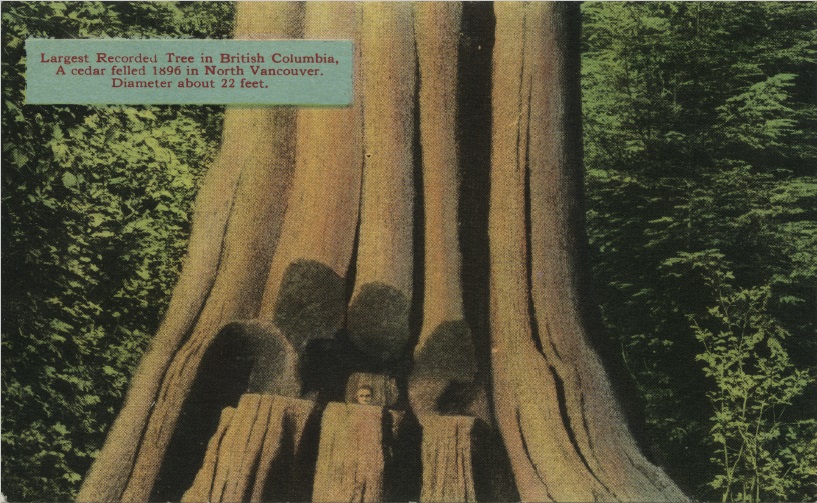

Source: Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. UL_1633_0034. Rare Books and Special Collections.

Just as this image shows evidence of colonial-settler disrespect for the land when looking at it with contemporary eyes, it also represents a casual disregard, or even wilful ignorance, of Indigenous beliefs. The cedar tree in particular “plays an integral role in the spiritual beliefs and ceremonial life of coastal First Nations,” as explained by Alice Huang, writing for UBC’s Indigenous Foundations resource. “The deep respect for cedar is a rich tradition that spans thousands of years and continues to be culturally, spiritually, and economically important.”11

Top-left: View of the Princess Charlotte steamer ship leaving Vancouver for Victoria.

Source: Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. UL_1624_03_0092. Rare Books and Special Collections.

Top-right: View of the St. George, North Vancouver ferry No. 2. Written on photograph: No. 47.

Source: Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. UL_1624_02_0307. Rare Books and Special Collections.

Bottom: View of a steamer leaving Nanaimo, spewing smoke. The town can be seen in the background.

Source: Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. UL_1638_0013. Rare Books and Special Collections.

These three images portray the types of boats that settlers introduced into the area. The first image is a larger ship that would undertake trips of longer duration to more distant locations, and the latter two photographs depict smaller ferries in North Vancouver and Nanaimo, respectively, that would have made shorter journeys once a day. All three images demonstrate how much air and water pollution each vessel produced in the single instant it took to capture the photographs. From this, we can imagine how much pollution would have resulted from daily passages of each ship. At the time they were taken, these photographs may have been innocuous snapshots documenting travel practices of the time. They may even have acted as praiseworthy evidence of the modernization of Vancouver society. Contemporary viewers might be more likely to see the images from the perspective of environmental concerns, and consider the idea of progress differently.

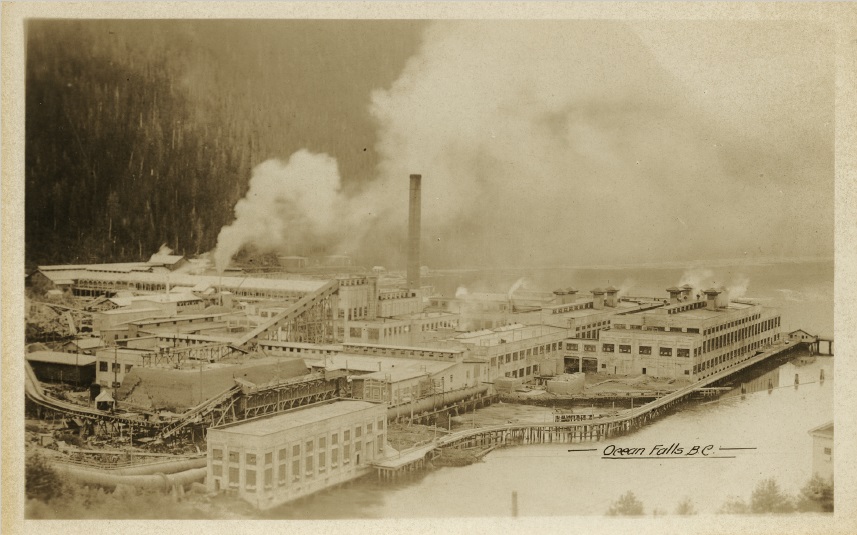

Source: Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. UL_1635_0026. Rare Books and Special Collections.

Image description: Aeriel view of factories and other buildings in downtown Vancouver.

Source: Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. UL_1624_03_0338. Rare Books and Special Collections.

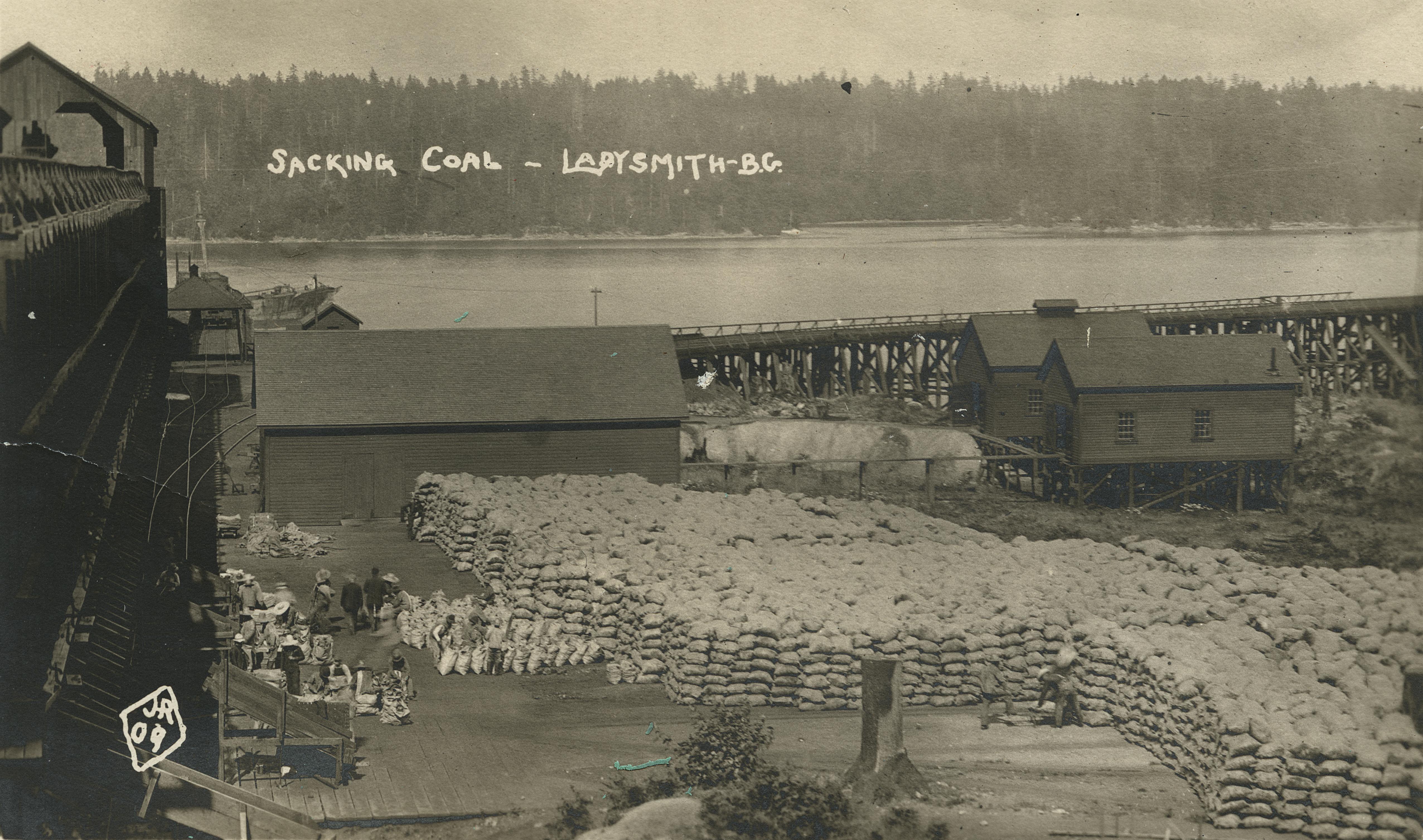

This image shows the scope of a mining operation in Ladysmith, B.C. The photographer has used a wide-angle shot to give viewers an impression of how much coal the mine has produced. This photographic tactic is similar to one that photographers employed to depict mass deforestation in several of the images above.

Source: Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. UL_1656_0004. Rare Books and Special Collections.

Modern Impacts

The dispossession of Indigenous lands and waters is one that continues to be relevant today, as many settlers continue to disregard Indigenous rights. For example, settlers recently harassed Mi’kmaq Nation fishers on the east coast of Canada for exercising their traditional fishing rights. Unlike similar incidents throughout Canadian history, this battle ended in success for the Mi’kmaq, wherein several communities were able to come together to purchase a controlling stake in the Clearwater12 fishing company, thereby legally strengthening their traditional right to fish.13

Similar battles for land and water rights have been occurring across the country for many years. In British Columbia last year, tensions between the Wet'suwet'en nation and the federal and provincial governments came to a head over a proposed gas pipeline, commissioned by Coastal GasLink, to be laid in unceded Indigenous territories.14 When the pipeline was approved by the B.C. Supreme Court, mass protests broke out across the country, and continued on Wet’suwet’en territory, in support of Indigenous people’s rights to refuse access to their lands.15 As of the creation of this exhibition, work on the pipeline has gone ahead in spite of those protests and the COVID-19 pandemic.16

Collection as Data (click to download)

Metadata CSV Metadata JSON Geodata JSON Timeline JSON Facets JSON Source Code

2. Ken Drushka, Canada’s Forests: A History (Durham, North Carolina: Forestry History Society, 2003), 27.

3. Ken Drushka, Canada’s Forests: A History (Durham, North Carolina: Forestry History Society, 2003), vii.

4. Max Liboiron, “Pollution is Colonialism,” Discard Studies, September 1, 2017, https://discardstudies.com/2017/09/01/pollution-is-colonialism/.

5. “Musqueam: giving information about our teachings,” Musqueam First Nation and Museum of Anthropology, accessed November 12, 2020, https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&ved=2ahUKEwio3bT0kP7sAhUQs54KHTBGDdsQFjAAegQIAhAC&url=https%3A%2F%2Fmoa.ubc.ca%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2018%2F02%2FTeachers-Resource-ENGLISH-March30_sm.pdf&usg=AOvVaw0eiIusSMK0hdy1P06SiolY.

6. Winona LaDuke, All Our Relations: Native Struggles for Land and Life (Haymarket Books: Chicago, IL, 2016), 2.

7. “McKenna-McBride Commission,” BC Learning Network, accessed January 22, 2021, https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&ved=2ahUKEwj3kMv4oavuAhVeIDQIHT6YAkwQFjAEegQIBBAC&url=http%3A%2F%2Fbclearningnetwork.com%2FLOR%2Fmedia%2Ffns12%2Fpdf%2FModule2%2F2.4%2520A1%2520McKenna-McBride%2520Commission.pdf&usg=AOvVaw2OrRL4MMt4btvfOPrN0yLd.

8. Ibid.

9. Daniel Heath Justice, Why Indigenous Literatures Matter (Ontario, Canada: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2018), 87.

10. Cole Harris, The Resettlement of British Columbia: Essays on Colonialism and Geographical Change (Vancouver, BC: UBC Press, 1997), 82.

11. Alice Huang, “Cedar,” last modified 2009, accessed November 12, 2020, https://indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/cedar/.

12. Clearwater originated as a small lobster retailer in Nova Scotia and grew to become one of the world’s largest seafood companies. “About Us,” Clearwater Seafoods, accessed January 25, 2021, https://www.clearwater.ca/en/our-story/history/.

13. Leyland Cecco, “'We won': Indigenous group in Canada scoops up billion dollar seafood firm,” The Guardian, November 12, 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/nov/12/canada-clearwater-seafoods-mikmaq-first-nation-fishing.

14. Chantelle Bellrichard, Jorge Barrera, “What you need to know about the Coastal GasLink pipeline conflict,” CBC News, February 5, 2020, https://www.cbc.ca/news/indigenous/wet-suwet-en-coastal-gaslink-pipeline-1.5448363.

15. Bethany Lindsay, “B.C. Supreme Court grants injunction against Wet'suwet'en protesters in pipeline standoff,” CBC News, December 31, 2019, https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/bc-injunction-coastal-gaslink-1.5411965.

16. Gordon Jaremko, “Coastal GasLink Pipeline Progressing; TC Energy Optimistic for Keystone XL,” Natural Gas Intelligence, November 18, 2020, https://www.naturalgasintel.com/coastal-gaslink-pipeline-progressing-tc-energy-optimistic-for-keystone-xl/.

![[View of a mill]](/langmann-2021/objects/ul_1639_0012_02.jpg)

![[View of cut logs]](/langmann-2021/objects/ul_1639_0012_03.jpg)

![[Steamer] Leaving Vancouver](/langmann-2021/objects/ul_1624_03_0092.jpg)