And They Called It Vancouver

Settler-Colonial Relationships to Indigenous Lands and Peoples

Relations with Indigenous Peoples

Part of the project of colonization required settlers to actively suppress the perspectives, wishes, and needs of Indigenous peoples. As the photographs in the Langmann collection were mainly taken by settlers, they profoundly attest to this suppression, and serve to illustrate its effects. The previous two exhibit sections explored settler relationships to Indigenous lands, both in terms of the ways they developed it once it had been stolen, and in terms of their disregard for environmental custodianship. Due to the nature of the relationships between Indigenous peoples and their ancestral lands, a discussion of settler relationships to Indigenous lands necessarily requires consideration of settler relationships to Indigenous peoples themselves. This section moves away from a specific focus on land to address the treatment of Indigenous peoples, histories, traditions, and customs. The images testify to the violent and problematic relationship that settlers cultivated with Indigenous peoples.

It is important to also note here the ways in which Indigenous peoples attempted to assert their rights and agency and were continually shut down by colonial settlers and the Canadian and British governments. One prominent example is the effort made by Squamish leader Su-á-pu-luck, more commonly known as Joe Capilano. Seeking redress for the lands that had been stolen, as well as the ever-increasing amount of hunting and fishing regulations, Su-á-pu-luck led a delegation of elders first to Ottawa to meet with Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier, and then to England to meet King Edward VII.1 He and his fellow delegates, Basil David of the Shuswap and Chillihitza of the Okanagan, presented a petition to the king which addressed grievances related to the facts that “aboriginal title to the land had never been extinguished, that settlers had moved onto the land without its owners’ approval, that appeals to the Canadian government had been fruitless, and that [Indigenous] people[s], who lacked the vote, were not even consulted by Indian agents on matters affecting their lives.”2 Although Su-á-pu-luck and many other Indigenous activists continued to fight for their land rights for the rest of their lives, the Canadian and British governments never addressed their concerns or demands in any meaningful way.

Trigger warning: Viewers should be advised that this section contains information about the historical treatment of Indigenous peoples in Canada, which may be upsetting. The topics we touch on include desecration of grave sites; the residential school system; cultural appropriation of Indigenous clothing; the forced Christianization of Indigenous peoples; and settler disrespect and/or ignorance of Indigenous customs, traditions, and land rights, among other topics.

This section also contains an image of an animal that has been killed for sport.

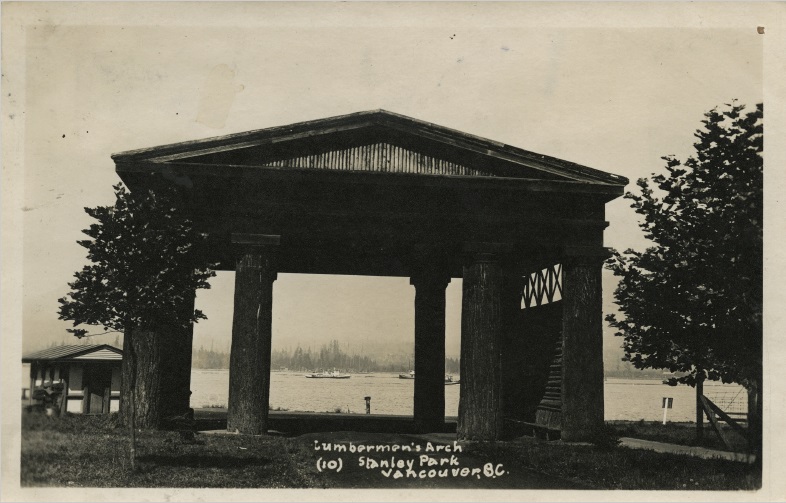

In 1912, the original Lumberman’s Arch, made up of eight thick tree trunks, was installed across Pender Street in downtown Vancouver to commemorate the visit of the Canadian governor general, the Duke of Connaught.3 The following year, the arch was relocated to the area now known as Stanley Park. John Mackie, a journalist at the Vancouver Sun, explains how the arch was resituated “on the site of an old native village that whites called Whoi Whoi,” or Xwayxway, home to Squamish, Musqueam and Tsleil-Waututh First Nations.4

Source: Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. UL_1624_02_0127. Rare Books and Special Collections.

The focus remained on grooming Stanley Park to become a decoration to the city, rather than on the area’s Indigenous population. A newspaper article written at the time of the relocation of Lumberman’s Arch celebrated it as a “permanent advertisement of our lumber industries, a memento of the Royal visit and, artistically placed, a real ornament and appropriate addition to our beautiful park.”7

Other locations around what is now known as Metro Vancouver that had once been sites of thriving Indigenous communities were subjected to similar desecration by settlers. A three-site exhibition at the Musqueam Cultural Education Resource Centre, UBC's Museum of Anthropology, and the Museum of Vancouver in 2015 helped tell the story of c̓əsnaʔəm, a robust village and burial site at the edge of the Fraser River where Musqueam people lived, worked, and raised their families for 5000 years. Jordan Wilson, a co-curator of the exhibition and member of the Musqueam nation, describes how, “as late as the 1960s, it was common practice for Vancouver families to come and dig for artifacts, without understanding the significance of the location or making the connection to the Musqueam community.”8

This image shows us another relic of the many past lives of Stanley Park, from a zoo which existed there from 1888 to 1996.9 As Jesse Donaldson of The Tyee says, “Not only were plant species regularly added and replaced in the Stanley Park of the early 20th century; so too were members of the peninsula’s animal population” such as “animals kept in the park zoo (including several deer and a bear notable for its repeated escapes).”10 Stanley Park remained full of nature, but only in ways that felt palatable and safe to Vancouver’s settler residents.

Source: Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. UL_1624_02_0261. Rare Books and Special Collections.

Source: Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. UL_1649_0003. Rare Books and Special Collections.

“We learned to be human in large part from the land and our other-than-human relatives… and our humanity is enhanced and enriched by actively – and imaginatively – engaging them again and again in respectful relationship. This doesn’t mean considering them to be the same as us, as they aren’t, but their difference isn’t deficiency – it’s simply difference, and is to be honoured as such, because each person’s difference brings new skills to help us survive and flourish as peoples.”11

We can see how at odds this perspective would have been with the attitude represented in this image.

Source: Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. UL_1624_02_0242. Rare Books and Special Collections.

“When British Columbia entered Confederation in 1871, Aboriginal people were placed under federal jurisdiction. By 1876, the Indian Act legislated our daily lives. In an attempt to assimilate Aboriginal people to Christian Canadian society, the government sent our children to Indian residential schools. Despite these destructive policies, our culture and society persisted.”13

Source: Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. UL_1624_03_0177. Rare Books and Special Collections.

This image portrays an Indian residential school in Chilliwack, with the innocuous and euphemistic handwritten caption, “Coqualeetza Industrial School.” The residential school system is widely considered to be one of the greatest crimes perpetrated against Indigenous peoples by the Canadian government. In an effort to separate Indigenous children from their families, cultures, and traditions, the children who were sent to these institutions were “taught that their cultures were inferior and that they themselves were worthless. They suffered all manner of abuse: physical, emotional, sexual, psychological, and spiritual.”14 There were a total of at least twenty-two residential schools in British Columbia alone, the last of which did not close until 1984, and more than 150,000 children across Canada were forced to attend. Survivors of the residential school system and their families are still grappling today with the inter-generational trauma that these institutions caused.

Justice expands upon the intended impacts of the residential school system, explaining how “one of its fundamental purposes was to dismantle Indigenous resistance through a direct, sustained attack on families and the full network and relations and practices that enabled health and self-determination.”15 Because of this, the full effects of the residential school system take on a more profound meaning when one begins to understand the importance of kin and relation in Indigenous communities, and how damaging an attack on those connections would have been. Justice also explains, in this context, the power of healing: “What the authorities didn’t take into account was the capacity for old bonds to be rewoven and new links to be formed as people began to share their stories and experiences, in person and in print. Shame and silence were no match for story; the suppressed truths couldn’t remain hidden forever.”16 This is an important reminder not only of the power of storytelling, which is the focus of Justice’s book, but also of the power and resilience of Indigenous peoples.

More information can be found through the Indian Residential School History and Dialogue Centre, which aims to address this history from a Survivor-centred approach.17

This image portrays a White settler child who has been dressed up in traditional Indigenous clothing as a “mascot” for the Vancouver Golden Jubilee celebration. Not only does the image represent willful cultural appropriation, it also betrays the settler-colonial erasure of diversity of Indigenous peoples. The feather headdress and style of beading found on this outfit were not typically used by Indigenous peoples of the Northwest Coast; the outfit is therefore a trope or generalization of what White settlers thought of as Indigenous clothing. Similar inaccuracies were rampant among photographs taken of Indigenous individuals by settlers across North America at the time, including but not limited to the misidentification of nations, tribes, or individuals, or the use of stage props such as bows and arrows, tomahawks, and buckskins.18

Source: Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. UL_1624_02_0240. Rare Books and Special Collections.

Furthermore, the image is particularly poignant when considered in conversation with the previous image of a residential school, since Indigenous children in residential schools were frequently punished for attempting to maintain the traditions of their people, including language and clothing. The use of Indigenous peoples and imagery as “mascots” is an affront that continues today and is fought against by Indigenous peoples across North America. Cultural appropriation, including stealing aspects of minority clothing, cultural expressions and symbols, ways of knowing, and more, also remain prevalent to this day.

Source: Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs. UL_1624_03_0246. Rare Books and Special Collections.

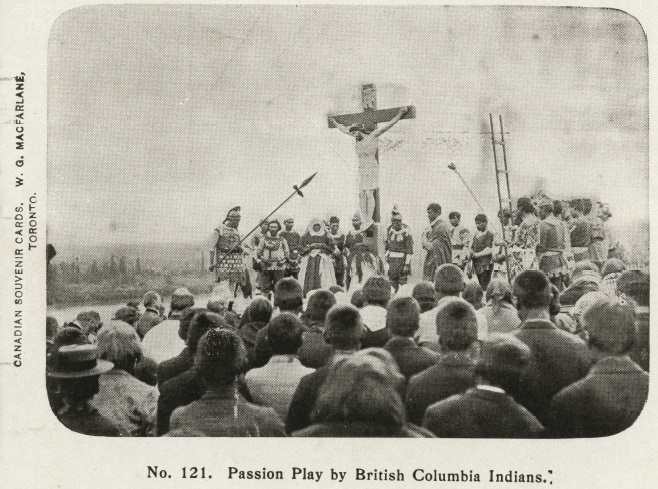

“If the potlatch, the cornerstone of the culture of coastal First Nations, could be eradicated, then the government and the missionaries would be free to swoop in and fill the cultural void with Christianity.”19

The Christianization of Indigenous peoples also offered another pathway by which settlers could justify colonization to themselves. By believing that they had been given a mandate by god to convert and assimilate Indigenous peoples, churches and missionaries provided a moral pretext to crimes that they might otherwise have found difficult or impossible to excuse.

Collection as Data (click to download)

Metadata CSV Metadata JSON Geodata JSON Timeline JSON Facets JSON Source Code

2. Ibid.

3. “Vancouver Feature: Timber Arch Installed on First Nation Site,” The Canadian Encyclopedia, September 6, 2019, https://thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/vancouver-feature-timber-arch-installed-on-native-site

4. Mackie, John. “This Week In History: 1947 Lumbermen's Arch is demolished.” Vancouver Sun (Vancouver, BC), Dec. 2, 2016. https://vancouversun.com/news/local-news/this-week-in-history-1947-lumbermens-arch-is-demolished.

5. Jean Barman, Stanley Park’s Secret: The Forgotten Families of Whoi Whoi, Kanaka Ranch and Brockton Point (Madeira Park, BC: Harbour Publishing, 2005), 21.

6. “Archaeology in B.C.,” Government of British Columbia, December 18, 2020, https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/industry/natural-resource-use/archaeology.

7. Mackie, John. “This Week In History: 1947 Lumbermen's Arch is demolished.” Vancouver Sun (Vancouver, BC), Dec. 2, 2016. https://vancouversun.com/news/local-news/this-week-in-history-1947-lumbermens-arch-is-demolished.

8. Margaret Gallagher, “Groundbreaking c̓əsnaʔəm exhibition traces Musqueam's past,” CBC News, January 22, 2015, https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/groundbreaking-c-%C9%99sna%CA%94%C9%99m-exhibition-traces-musqueam-s-past-1.2927167.

9. Stevie Wilson, “The Stanley Park Zoo, A Vancouver Institution Until 1996,” Scout Magazine (Vancouver, BC), December 4, 2014, https://scoutmagazine.ca/2014/12/04/you-should-know-more-about-the-stanley-park-zoo-a-vancouver-institution-until-1996/.

10. Donaldson, Jesse. “An Unnatural History of Stanley Park.” Tyee (Vancouver, BC), Sept. 27, 2013. https://thetyee.ca/Life/2013/09/27/Unnatural-History-of-Stanley-Park/.

11. Daniel Heath Justice, Why Indigenous Literatures Matter (Ontario, Canada: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2018), 76-77.

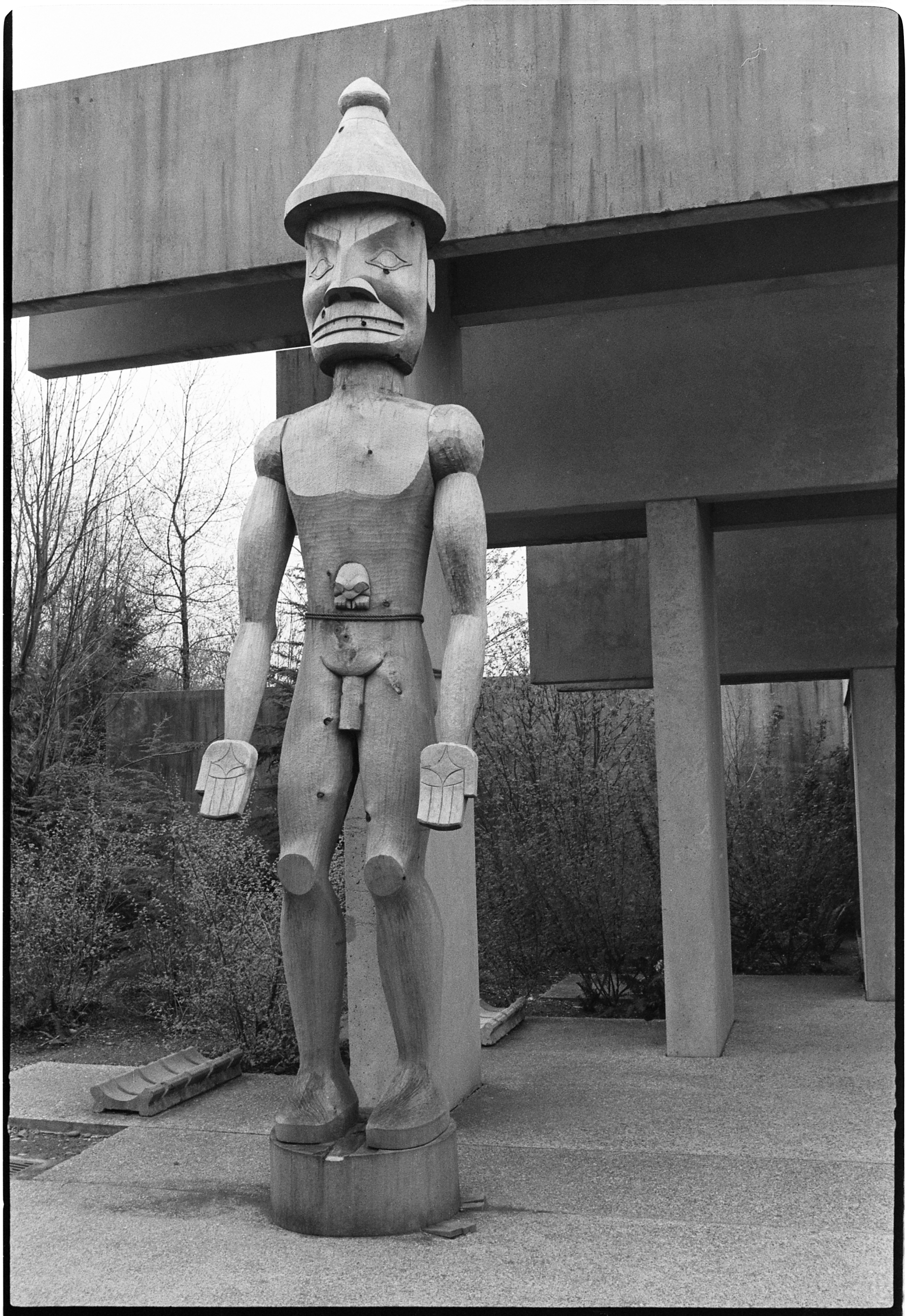

12. Steve Weisman, “Joe David ‘Meares Island’ welcome figure,” September 1, 2015, https://atom.moa.ubc.ca/index.php/crew-and-log-at-old-ubc-carving-shed-and-at-moa-33.

13. “Historic Timeline,” Museum of Anthropology Musqueam Teaching Kit, accessed December 14, 2020, http://www2.moa.ubc.ca/musqueamteachingkit/history.php.

14. “Project of Heart: Illuminating the hidden history of Indian Residential Schools in BC,” BC Teachers’ Federation, August 2015, https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&ved=2ahUKEwjE5fXd9eLtAhWYsJ4KHWp0D0kQFjACegQIARAC&url=https%3A%2F%2Fbctf.ca%2FHiddenHistory%2FeBook.pdf&usg=AOvVaw2ZVS8k_i_HmwryqUbe6oOI.

15. Daniel Heath Justice, Why Indigenous Literatures Matter (Ontario, Canada: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2018), 85.

16. Daniel Heath Justice, Why Indigenous Literatures Matter (Ontario, Canada: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2018), 85.

17. “What we do,” Indian Residential School History and Dialogue Centre, accessed December 14, 2020, https://irshdc.ubc.ca/about/what-we-do/.

18. Jakob Dopp, “Looks Can Be Deceiving: Issues Regarding 19th-Century Native American Photographs,” Clements Library Chronicles, University of Michigan, December 23, 2019, https://clements.umich.edu/issues-regarding-19th-century-native-american-photographs/.

19. Bob Joseph, “Potlatch Ban: Abolishment of First Nations Ceremonies,” Indigenous Corporate Training, Inc., October 16, 2012, https://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:1H8pzdD8UuwJ:https://www.ictinc.ca/the-potlatch-ban-abolishment-of-first-nations-ceremonies+&cd=3&hl=en&ct=clnk&gl=ca&client=firefox-b-e.

20. Karin Marley, “Majority of indigenous Canadians remain Christians despite residential schools,” CBC News, April 1, 2016, https://www.cbc.ca/radio/thecurrent/the-current-for-april-1-2016-1.3516122/majority-of-indigenous-canadians-remain-christians-despite-residential-schools-1.3516132.

21. Christianity and First Peoples, Open Library Pressbooks, accessed December 23, 2020, https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/indigstudies/chapter/christianity-and-first-peoples/.

22. Tolly Bradford and Chelsea Horton, Mixed Blessings: Indigenous Encounters with Christianity in Canada (Vancouver, BC: UBC Press, 2016), 3.

23. Ibid.