Description

This digital exhibition features photographs and postcards from the Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs, housed at UBC's Rare Books and Special Collections.

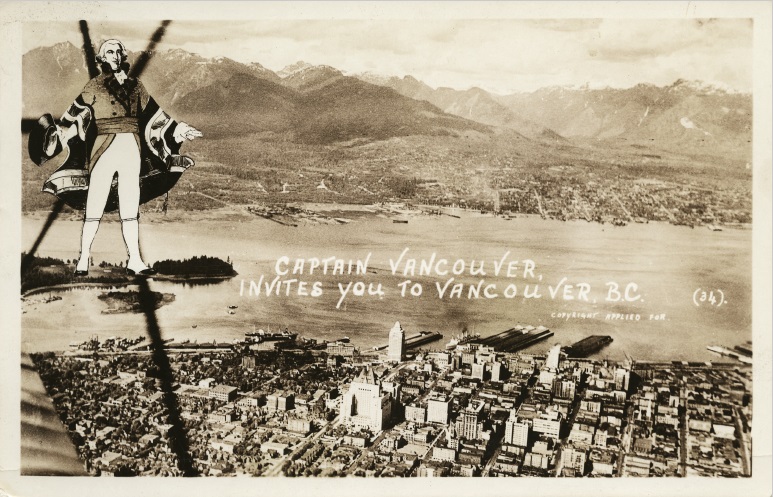

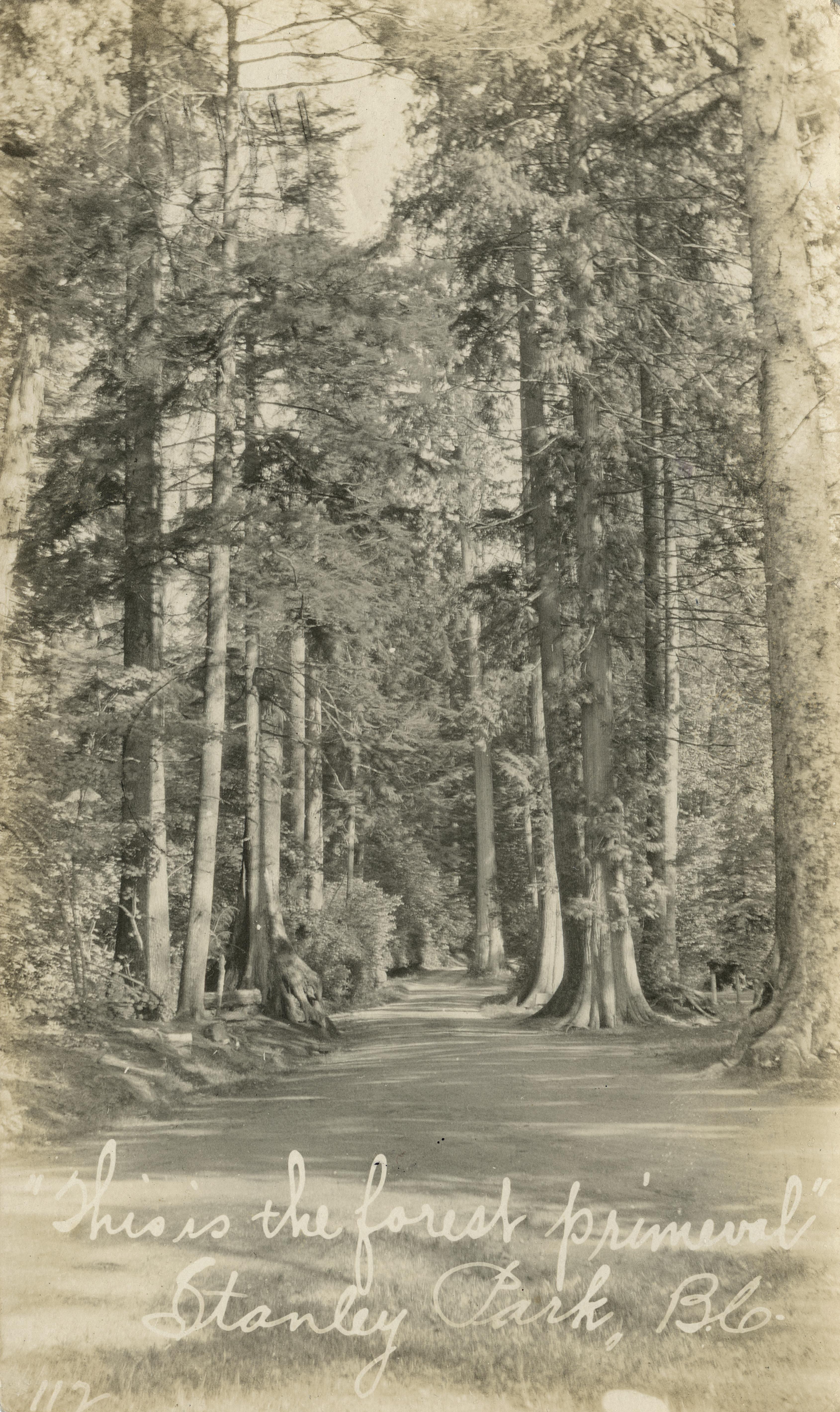

Learn More »The Uno Langmann Family Collection of B.C. Photographs consists of more than 18,000 photographs taken in or near British Columbia between the 1850s and the 1970s. The photographs depict scenes that give us insight into the history of this area, showing us burgeoning industries of that time, including logging, fishing, and mining, as well as where and how average settlers1 spent their leisure time. This exhibition features a selection of photographs from the Langmann collection, which represent the perspective of White settlers in the late 19th and early 20th century.

Around the turn of the 20th century, the time period when most of the photographs were taken, British Columbia had just recently become a province, but the settler-colonial presence in the area was nothing new. For decades already, settlers had been encroaching upon the traditional, ancestral, and unceded territories of Indigenous peoples. As Cole Harris, a professor emeritus at the University of British Columbia focused on geographies of colonialism, describes, “Natives had been allocated small reserves where, their numbers much reduced and their voices unheard, they lived at the margins of a non-Native world.”1

Time Span

1890s to 1936

View Timeline

Objects

33

Images

View table

The vast majority of photographs in the Langmann collection were taken by colonial-settlers, and as such, many of them are situated within a particular worldview, with particular relationships to both Indigenous peoples and Indigenous lands. Both were taken for granted as things to be tamed and overcome in what was then widely seen as a natural, inevitable, and triumphant progression toward urban development and modernization. As Paige Raibmon expresses while reflecting on her experience working with the Langmann photographs “These images were illustrations in a larger colonial fairy tale that reassured settlers their occupation was uncontested.”3

Today, in the early twenty-first century, as many of us aim to think more critically about the consequences of colonization, it is worth examining or re-examining the spirit behind these photographs. This exhibition aims to highlight some of the photographs in the collection which most intensely embody the colonial-settler mindset, with the goal of encouraging viewers to think more critically about the actions and choices that settlers of that time espoused without question, and how those actions and choices impacted both Indigenous peoples and their lands, as well as how Indigenous peoples empowered themselves and advocated for themselves.

This digital exhibition is divided into three sections. Urban Development displays photographs that speak to a philosophy that dictated the natural world should be suppressed in favour of developing carefully manicured urban environments. Environmental Impact shows examples of the effect curation of an urban society had on the natural environment. While the first two sections examine the relationships between settlers and Indigenous lands, the third, Relations with Indigenous Peoples, more directly addresses the prejudices and racist ideology of European settlers towards Indigenous peoples, cultures, histories, and their traditions.

Curator's Note

I first began curating this exhibition in the autumn of 2020, almost exactly three years after my first exhibition of photographs from the Uno Langmann collection. At that time, I was struck by how many items in the collection contained scenes of British Columbia that were familiar to me, even though most of them had been taken nearly a century before I was born, and my curatorial concept for that first exhibition, which I wrote about here, centered on the unchanging nature of architecture, gathering spaces, and natural landscapes across time.

When I dove back into the Uno Langmann collection this time, something quite different stood out to me. Although most of the images in the collection were taken approximately one hundred years ago, a mere blink of an eye on a historical scale, it seemed to me that many of the photographs were relics of their time, in the sense that they showcased scenes and themes with apparent pride that we today might see with a more critical eye.

An important note about the photographs in this exhibition is that, we cannot be certain of the photographers’ intentions. Within the text of the exhibition, I take the liberty of hypothesizing about the purpose of the photographs – why someone at that time would have wanted to document wide swaths of forest that have been logged, or animals that have been killed for sport, or parades marching through downtown Vancouver. Without being certain of the reasons why these photographs may have been captured, these hypotheses are simply meant to express my own interpretation of the photographs, as I parsed through each and every one at the beginning of my curatorial process. I couldn’t help but witness the images through a lens that more critically examines the issues that so many of us care about today: the environment, the fact that we live on stolen lands, what it means to live in a post-industrial world.

The closer I looked at the collection, the more I seemed to find images that fell into one of those three categories. The knowledge of how these lands were stolen and the peoples indigenous to these lands brutally oppressed became the backdrop to how I viewed the entire collection and the exhibition. Images of trees being cut down and smokestacks being raised were not celebrations of burgeoning industry in a young province; they were examples of the destruction of the natural environment. Images of new buildings downtown and the creation of Stanley Park were not examples of progress towards modernization; they were examples of settlers confidently making grand plans for lands that did not and do not belong to them. Some of the images, no matter what their original purpose may have been, became visual evidence of a flagrant disrespect and disregard for Indigenous peoples.

In that sense, the photographers’ intentions in taking the photographs become moot. The purpose of the exhibition is not to uncover the original purpose behind the photographs, but to examine what the photographs can tell us – intentionally or unintentionally, consciously or subconsciously – about the ethos of the time, and how much or how little settlers considered issues like environmentalism, industrialism, and Indigenous peoples’ rights. What is in the photographs, and what is absent from the photographs, is in that sense equally important.

One of the strengths of historical photographs – and indeed, history in general – is that it can cause us to think more critically about our role in it. How have our pasts shaped us? How will we shape the future? I hope this exhibition encourages us, particularly those of us living on stolen lands, to think more critically about our own roles in the narratives presented here: our relationships to the environment, our relationships to urban development, and our relationships to and with Indigenous peoples. I hope we can more clearly see what’s there, as well as what may be missing.

- Ashlynn Prasad

Collection as Data (click to download)

Metadata CSV Metadata JSON Geodata JSON Timeline JSON Facets JSON Source Code

2. Paige Raibmon, “Posing the Past,” in Nanitch: Early Photographs of British Columbia from the Langmann Collection, a co-production of Presentation House Gallery and the University of British Columbia Library (North Vancouver: Presentation House Gallery, 2016), 58.

![[Illustration for the Golden Jubilee of Vancouver]](/langmann-2021/objects/ul_1624_02_0239.jpg)