Homelife

Contents: Homesickness Making a Home Recreation

Homesickness

Only just over a month passed between the declaration of war on Japan by Canadian Prime Minister Mackenzie King, and the Order in Council that began to strip Japanese Canadians of their homes, livelihoods, and property. By spring of 1942, most families were already being sent against their will to various internment sites and sugar beet farms across the country.

Because of how quickly this uprooting took place, we can see in the correspondents’ earliest letters with Joan their individual ways of coping with the loss of their homes, their communities, and their safety.

Many correspondents expressed a great longing for British Columbia; for most of them, New Westminster and the areas surrounding it were the only home they had ever known. Weather comparisons and romantic descriptions of West Coast landscapes can be found in a number of the letters.

Gosh I will miss the cherry and other fruits and even the flowers. Anyhow I remember seeing a tulip before I came here.

To tell you the truth I think British Columbia is the best place to live and enjoy scenery.

Everywhere you look, just level plains of farming lands can be seen, while back in B.C: everywhere you look are trees and nothing but trees. Not one speck of the beautiful mountains can be seen either. We all miss our beautiful B.C. trees and mts.

For others, this homesickness was more closely tied to their school community at Queen Elizabeth Secondary. Joan received frequent requests for copies of the school newspaper, the Q.E. Vue, in addition to updates on teachers and the results of school sporting events. One correspondent, Yoshio Nakamura, spends the first six months of 1944 requesting that Joan send a school pin. When Joan is able to finally fulfill this request, Yoshio reminisces about their shared time at school and compares his years pulled away from home to those of a soldier fighting on foreign soil.

Yoshio Nakamura to Joan Gillis, June 26, 1944

"I do not know how to thank you for that swell pin. You do not know how I felt when I touched it and looked at for a long time. That pin alone brought back the memories that I have cherished for so long. It reminded me of Q.H.S. and of the students that were in it and are in it now. It brought me back to the time I shook hands with you on that last day at school. Gosh, but I wish I could live those years over again. I feel like a soldier away on a foreign shore fighting in battles, and thinking the peaceful hours spent before the tragic occurance [sic]. Thank you an awful lot Joan, for the pin. I won't forget it."

Making a Home

Though assignment to sugar beet farms was framed by the federal government to be a choice that afforded Japanese Canadians the “privilege” of keeping their families together, the number of members in a family who were old enough to work in the fields was a large consideration for the farmers who selected which families to employ.1 However, the housing provided by these farmers was often no more than a single-room storage shed. The B.C. Security Commission, who enforced the dispersal of Japanese Canadians and the non-consensual sales of their property, provided some additional lumber for makeshift extensions to farm homes, but only distributed it to the land-owning farmers.2

Housing conditions came as a shock to many of Joan’s correspondents, particularly for those whose families had owned their own farms or businesses in B.C. Jackie Takahashi describes his new quarters as a “wee shack” of “10’ by 20’”, with no room for anyone to move.3

Not too far from Jackie was Sumi Mototsune, who was sent to live and work on a sugar beet farm near Raymond, Alberta, with her parents, three sisters, and one brother. In a letter from May 30th, 1942, she says of her family's one-room home, “Only mice can have the pleasure of living in here.”

Despite the many difficulties of their new living conditions, we can see the ways that the correspondents and their loved ones fought to build a home. Sumi and her mother ask Joan for flower seeds from British Columbia to populate their home garden. Not long after the comment about only mice enjoying their home, Sumi also writes that her father is crafting a second-room extension to improve their house for their family.

In a much later letter from 1947, Jackie Takahashi notes that he is moving to Brooks, Alberta, to pursue better career opportunities but is hesitant to leave Magrath, the town which had become his home and which he notes is one of the only places in Alberta to grant Japanese Canadians municipal voting rights. He says, "I think when you get to know a place for a while you start to like it even if it is a dead place. Magrath is just a small store on a road but now I hate to leave it."4

Recreation

Between recollections of backbreaking labour in the beet fields and experiences of discrimination in their new environments, it can be difficult to remember that most of the letter-writers in this exhibit are just teenagers. One of the greatest reminders of the young age of these correspondents, and a reflection of their resilience in spite of ongoing systemic racism, is the enthusiasm with which they write to Joan about their hobbies, passions, and the activities they turn to for fun.

Sports games against rival schools are recounted point by point. The same dance socials are discussed by multiple correspondents, with palpable awkwardness and excitement. Accounts of weekend trips to go swimming and skating at the lakes are written in startling detail. Below, Albert Ohama writes about one of his favourite singers, Bing Crosby.

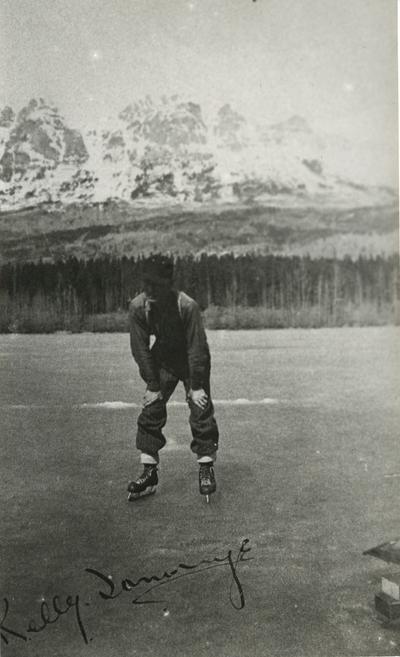

Image description: Person on skates in unidentified camp. Handwriting on the photo possibly reads Kelly Inouye.5

Music? I think I like Bing the bestest. I like smooth lingering music. Of course I classical [sic] -- but not too classical. One thing I don’t like --yet is that corny cave-man music (racket -- I mean). It actually drives me nuts.

Correspondents send detailed lists of films seen and songs recently heard on the airwaves to Joan. Perhaps more important than entertainment, these films and radio programs represented cultural links to home, a way of relating to a community of which they could no longer physically be a part.

1. Oikawa, Mona. “Economies of the Carceral: The ‘Self-Support’ Camps, Sugar Beet Farms, and Domestic Work.” In Cartographies of Violence: Japanese Canadian Women, Memory, and the Subjects of the Internment, 173. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2012.

2. Nakamura, Yoshio. “Richard Yoshio (Dick) Nakamura.” In Honouring Our People: Breaking the Silence, edited by Randy Enomoto, 189. Burnaby, BC: Greater Vancouver Japanese Canadian Citizens’ Association, 2016.

3. Takahashi, Jackie. Correspondence from Jackie Takahashi to Joan Gillis. 10 May 1942. RBSC-ARC-1786-01-24. Joan Gillis fonds. University of British Columbia Library Rare Books and Special Collections, Vancouver, Canada.

4. Takahashi, Jackie. Correspondence from Jackie Takahashi to Joan Gillis. 24 February 1947. RBSC-ARC-1786-01-33. Joan Gillis fonds. University of British Columbia Library Rare Books and Special Collections, Vancouver, Canada.

5. University of British Columbia Library. Rare Books and Special Collections. Japanese Canadian Research Collection. JCPC-30-003. https://dx.doi.org/10.14288/1.0049343