Communications

Contents: Photographs Letter Writing Censorship

When Japanese Canadians were forcibly displaced, they were also restricted in their ability to gain and distribute information. Access to radios and cameras in particular was severely limited, or often completely denied to forcibly uprooted Nikkei. Order In Council 1486 explicitly permitted the confiscation of short-wave radios and cameras by the RCMP, ostensibly because of concerns that Japanese Canadians would be using these sources of information for the benefit of Japan. It is not entirely clear in the context of these letters as to whether or not Japanese Canadians were explicitly told they were not allowed to have these materials.

Oh yes we got a privilege to own a radio and a camera here. We had both radio and two cameras there but we had to leave it in the hands of the R.C.M.P. I believe the custodian is now looking after it. ... We have sent for our camera about two weeks ago but it still hasn’t arrived

Were [sic] still allowed to have a camera yet, but since we haven’t one, we’ll have to borrow someones. We’re intending to take pictures before our cameras get banned, if they ever do.

Having the "permission" to do something, but not having the access or means is a recurrent theme throughout the letters. Just as Sumi's family wanted to take more pictures if they could, many of the teens would have preferred to stay in school rather than be in the fields, and many families would have relocated to better living situations had their requests not been denied by the B.C.S.C1. Tad's family waiting to receive their camera, but never actually getting it from the "custodian" of their property is also reflective of the conflicting messages of freedoms and restrictions that Japanese Canadians experienced throughout this period.

There is a theme across a large array of experiences from Japanese Canadians’ forced dispersal that relates to this idea of not quite being denied something, but also not actually being able to do something as a result of the measures and stigma associated with the Nikkei community during this period. A lack of money, a lack of agency, and a lack of resources played heavily into the quality of life that these families were able to have.

Photographs

While their access to picture-making equipment may have been limited or outright denied, photographs are clearly incredibly important to the letter writers, as evidenced by their many requests that Joan send them photos of herself or of home.

Photographs from before 1942, often saved in albums, offered an important way for Nikkei to remain connected with their pasts, and also to continue to foster a type of visual knowledge of changes to places and people that they missed.

As Japanese Canadians were uprooted from familiar communities throughout British Columbia and were overwhelmed by the loss of loved ones, photography was a way to re-centre themselves within a seemingly stable, yet imaginary, network of relations. Looking became an act of exchange with the subject – conflating the act of seeing with the act of knowing. At a time when all else familiar had been lost, photographs were the internee's ‘most cherished possession’

When they could, the letter writers also sent photos in return. When they did not have access to their own camera, traveling photographers offered a way for folks to have their photos taken.

To read more of what correspondents wrote about photographs,

check out the ‘Photographs’ tag on the subject visualization page.

Letter Writing

The visual communication of photographs and photograph exchange was made possible by the central activity that this exhibit celebrates: letter writing.

Just as photographs could provide visual reminders of home, letters from Joan represented one of the only sources of news from home available. Even if they could have had better access to media such as the radio or newspapers, several of the letter writers noted that it would be of little use because it would only be news of their present location.

We don’t get any newspaper so we don’t know anything. Whenever Dad goes to town, he buys a “Lethbridge Herald News” paper. It has only the half of the pages from that of Sun or Province, and there is no news of Vancouver or New Westminster. The other day, I sent a letter to “The Vancouver Daily Provinces” asking them if they can send a newspaper over here to Raymond. Do you think they will?

The news that Joan was able to provide in her letters was precious. Sumi describes her eagerness in receiving them in a letter to Joan dated May 16, 1942: "I recognized your writing on the envelope and ripped it open & read it immediately. The way how I threw down my hoe to read it, my mother knew who the letter was from. I read your letters, I don’t know how many times."

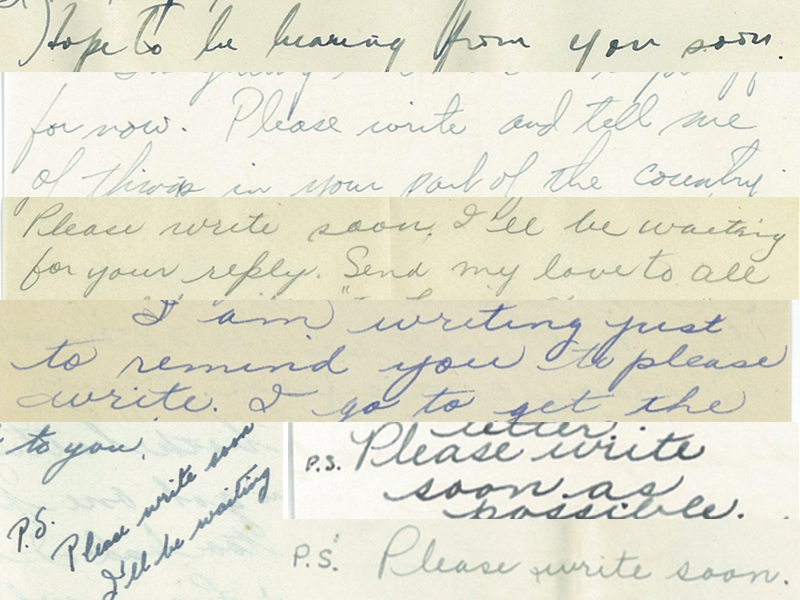

Example: Please Write Soon

Image description: A series of excerpts from multiple letters written by multiple authors featuring instances in which the correspondents asked Joan to write to them soon.

Postscripts asking Joan to write as soon as she could are common throughout the letters, as are descriptions of how her letters were able to give them a slice of the life they were missing.

But while Joan was able to provide many tales of Queen Elizabeth High School and what it was like at home in the New Westminster area, neither her letters nor those of the correspondents were free from the scrutiny of the Canadian government.

Censorship

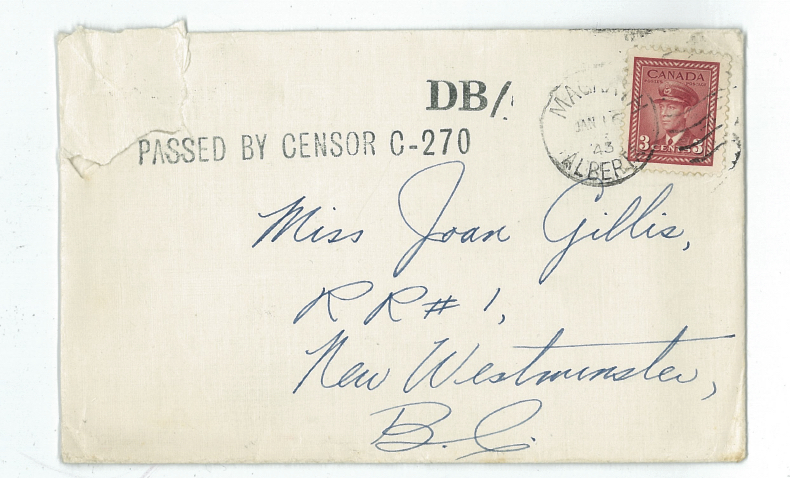

In addition to restrictions on certain forms of communication and information exchange, letters written to and by Japanese Canadians were subject to censure beginning in March of 1942. This process, in combination with the relative remoteness of many of the farms or towns that forcibly displaced families were sent to, greatly impacted how frequently letters could be sent and received.

Every letter we’re getting now is [censored] and just to send a letter 30 miles it takes over a week, because every letter we write goes back to B.C. to be [censored].

Of the letters from the Gillis fonds that are included in this exhibit, none of them were expressly censored by those that read them. It is possible that, through trial and error, the letter writers knew what not to include, or perhaps it is that there was much less concern on the part of the censor regarding what information about the conditions Japanese Canadians were living in was getting out to a white teenager in B.C. Either way, despite the fact that there are no marks of censorship on the letters, traces of their having read the letters remain in the form of stamps on the envelopes confirming their passing inspection.

We also see traces of censorship activity in the content of the letters themselves. While the information going to Joan may not have been censored, it appears that many of the letters that she sent to her friends were.

Example: The Old Peat Plant

No Joan, I do not know what kind of secret, if any, that old peat plant is, but I guess the censor does know what to censor eh what? — Letter from Yoshio Nakamura to Joan Gillis, August 26, 1942

Peat was used during WWII to pack munitions and in the construction of fire bombs. It is possible that information about the peat plant that Joan was working at was censored for this reason.

To read more of what correspondents wrote about writing, mail, and censorship,

check out the ‘Communications’ tag on the subject visualization page.

1. Shelly D. Ketchell, “Re-locating Japanese Canadian History: Sugar Beet Farms as Carceral Sites in Alberta and Manitoba, February 1942 – January 1943,” (MA Thesis, University of British Columbia, 2005), 6.

2. Namiko Kunimoto, "Intimate Archives: Japanese-Canadian family photography, 1939–1949," Art History 27, no. 1 (2004), 133.